A Journey into the Psyche: A Therapist's First Experience of Ego Death

What are Psychedelics?

Classic psychedelics include:

Psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms)

LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide)

DMT (Dimethyltryptamine), a primary psychoactive compound in Ayahuasca

Mescaline, found in the Peyote and San Pedro cacti

Traditional psychedelics primarily affect 5-HT₂A serotonin receptors in the brain, inducing profound changes in consciousness, emotions, and sensory perception. These effects often lead to experiences that some users describe as deeply transformative or mystical. While MDMA and ketamine have distinct mechanisms of action, they are also categorized as psychedelics due to their ability to induce altered states of consciousness.

The History of Psychedelics

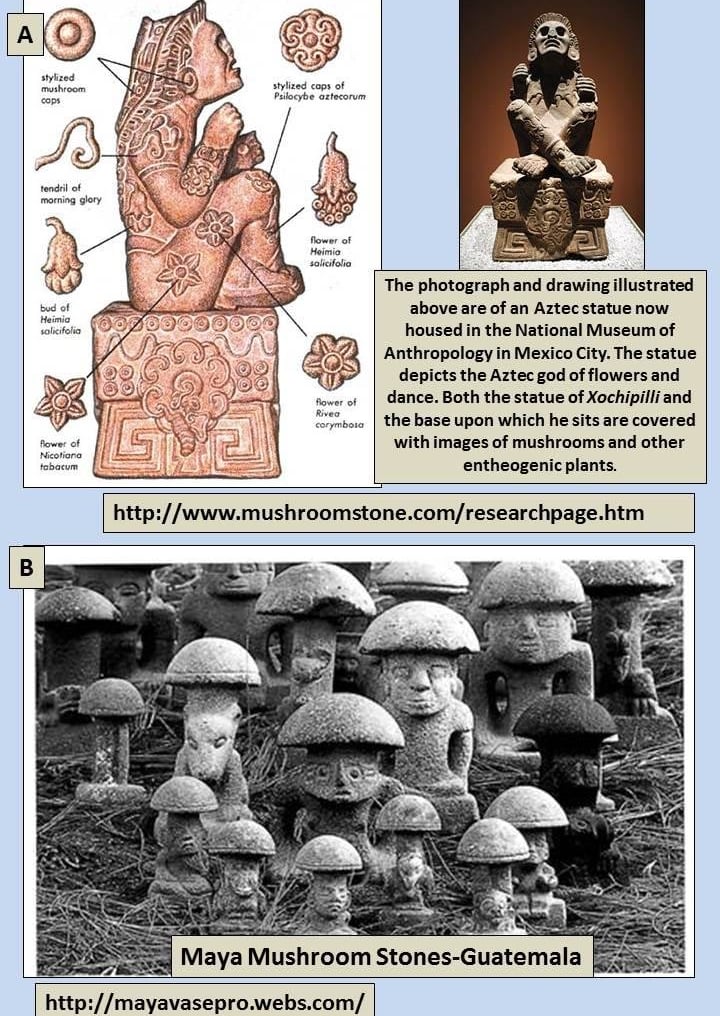

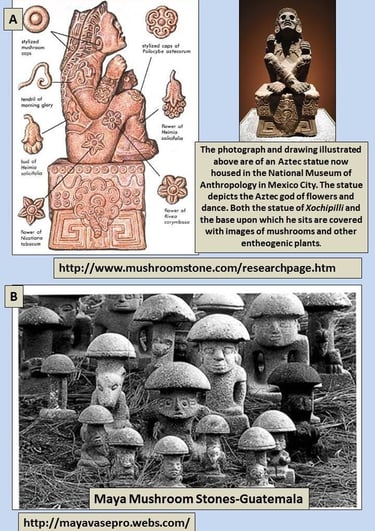

This classification reflects the natural origins of psychedelics, which have been used for thousands of years by Indigenous cultures across the Americas. Groups like the Maya, Aztecs, and various shamanic traditions have long incorporated these substances into healing practices, spiritual ceremonies, and personal growth.

By the late 19th century, chemists began isolating active compounds from these plants. In 1938, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD, marking the beginning of modern psychedelic research.

In the 1960s, psychedelics became entwined with the countercultural movement, which sought alternatives to mainstream values and lifestyles. The Human Potential Movement flourished, emphasizing self-exploration and personal growth. This era saw the rise of places like the Esalen Institute in California, the Omega Institute in New York, and the Haven Institute on Vancouver Island. My own involvement with the Haven in 2014 sparked my curiosity about inner exploration and deepened my dedication to helping others on their personal paths.

The cultural backdrop set the stage for the rapid development of psychology. Pioneers like Carl Jung, Abraham Maslow, Ken Wilber, Virginia Satir, and Fritz Perls, among others, contributed to the emergence of Humanistic Psychology, Family Therapy, Existential Psychotherapy, Gestalt Therapy, and Somatic approaches. Transpersonal Psychology, which explores expanded consciousness and deeper connections with the self and nature, also gained prominence. Psychedelics played a significant role in its development.

However, as drug abuse escalated and societal unrest intensified, the United Nations classified psychedelics as illicit substances by the late 1960s, bringing decades of research to a halt. It wasn't until the 1990s that scientific interest in psychedelics resurfaced, particularly in the treatment of depression, addiction, PTSD, and existential distress among cancer patients. The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and other organizations have led the revival of psychedelic research, with universities such as Johns Hopkins, UCSF, the University of Zurich and Imperial College London conducting groundbreaking studies.

Today, Ketamine is federally approved in the U.S. for treating treatment-resistant depression and PTSD. Oregon became the first state to legalize psilocybin for clinical use, with Colorado expected to follow. In California, Oakland and San Francisco have decriminalized psilocybin, though regulations continue to evolve.

Why I Chose Psychedelic Training

Growing up in China, I was taught the doctrine that “one drug experiment leads to a lifetime of suffering.” This instilled a strong aversion to all substances.However, as I immersed myself in professional development in trauma treatment, I began to understand the historical significance and therapeutic potential of psychedelics. Through preliminary experiences, I gained confidence in their healing effects. In June 2024, I enrolled in a year-long training program at the Integrative Psychiatry Institute (IPI), one of the most respected training organizations for Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy (PAT) in the U.S. The course focuses on the integration of Ketamine and Psilocybin into treatment, emphasizing techniques to safely guide clients through their psychedelic journeys, as well as the therapist’s own personal experiences.

My Medicine Journey

Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy (PAT) emphasizes "set and setting"—the user’s mindset and environment during the experience. Unlike recreational use, PAT is conducted in a safe and controlled environment, guiding individuals to turn inward, access inner wisdom, process unmetabolizedtrauma, and expand consciousness in ways that may foster spiritual connections.

The four-day practicum began by cultivating safety through connection with the space, partner, group, and facilitators. Participants alternated between experiencing the journey and acting as a sitter to support others. The final day was dedicated to integration—translating insights into daily life.

My journey began at 9:30 AM on the second day. I opted for the maximum allowed dose—34 mg of mushrooms—seeking the profound experiences often described in training and research. I also wanted to avoid a booster dose midway, unsure how my stomach would handle consuming them raw.

Following meditation and rituals to enhance body-mind presence, I prepared the dried mushrooms I had purchased the day before. Due to the unpleasant taste of dried mushrooms, many people prefer consuming them with food or drinks. I chose the Lemon Tek method—where mushrooms are ground into a fine powder and soaked in fresh lemon juice for 15-20 minutes. This approach is believed to make consumption easier, accelerate onset, and shorten duration.

After swallowing the lemon-infused mixture, I gave my partner a hug, thanking her for her support and companionship for at least the next five hours. I then lay down in my prepared "nest," put on headphones, and covered my eyes with an eye mask.

Eleven minutes into the journey, I felt a subtle warmth spreading through my body. I quietly told my partner, “The medicine is kicking in.” Having had prior experiences, I remained relatively calm for the first ten minutes. But before long, emotions surfaced, and I curled up to the left in a fetal position as tears began streaming down my cheeks.

I struggled to pinpoint the exact source of my sadness, yet I could clearly sense a deep sorrow rising from my chest. At times, I grieved for my inner child; at others, I mourned the pain carried by my partner, and the fellow journeyers in the room. What amazed me, even in that moment, was how my body embodied my mother’s painful retching sounds—the very ones I had often heard and witnessed during our weekly video calls. These experiences intertwined with fleeting images of my ancestors, likely tracing back to two generations before my grandfather, enduring oppression from bureaucrats and landowners during the feudal era. It soon dawned on me that the trauma I carried wasn’t just my own—it encompassed generational pain, the suffering of loved ones, and even distress of my clients.

After about an hour, panic began to set in. The labels that defined who I was—my name, where I lived, the work I was proud of, and even the faces of my family and friends—began to fade, drifting further and further into the distance. Despite my desperate efforts to hold onto them, they vanished. Eventually, I lost my ability to think in Chinese.

Despair consumed me. I became convinced that this was all a scam—that every event in my life leading up to this moment, including reading research papers on PAT, was part of a larger conspiracy to lure me into a restricted domain where I no longer had control over my body and thoughts, and I would merely become an object of manipulation.

"It’s over. I’ll never go back to normal," the thought echoed in my mind.

I remember trying to sit up multiple times, questioning my partner, “What is going on?” only to collapse back onto the mattress. I lost trust in everyone. Even the sight of the facilitators whispering to my partner—likely coaching her on how to support me—felt like yet another attempt to control me.

I’m unsure how long this state lasted, but around the second hour, I began to settle down as a mystical experience unfolded—one I am still trying to make sense of. I don’t fully remember how the shift occurred, but suddenly, I found myself cycling through various memories, revisiting familiar stores and places as if trapped in a film that played on an endless loop. A deep realization emerged: life itself felt cyclical, offering opportunities to return to certain points.

Then, an insight took root within me—perhaps there is no true death. “No wonder enlightened beings like Thich Nhat Hanh and some of my late mentors embraced death so gracefully. They understood that they would return, continuing their mission to illuminate the ‘truth’ for others, easing humanity’s fear of death. And it’s okay that some may never fully grasp this truth—because they have never had the opportunity to come close to such unexplainable experiences. But now you know, and you, too, will join the mission.”

At that moment, I felt a profound parallel between this realization and my own calling as a helping professional.

The journey continued for another 5 hours as I slowly recovered from the dissociative, dreamlike state. Many of the events I initially dismissed as medicine-induced hallucinations were later confirmed when I checked with the team the next day. These included briefly losing control of my bodily functions and needing to change, tiptoeing to the bathroom, dancing along to the live music while others watched, and reaching out for handholding as a source of support. These were actions I would have never imagined myself doing under normal circumstances, yet the medicine seemed to reveal new ways of being that I had not previously allowed myself to explore.

Integration: From Vision to Embodiment

One key feature of psychedelics is “information overload”—unlocking emotions, memories, and sensations otherwise inaccessible. While they can offer profound insights, integration is essential to making these experiences meaningful and transformative. As the saying goes, “Psychedelics show the door, but you have to walk through it.”

Research shows psychedelics enhance neuroplasticity, fostering new neural connections. In the weeks following my session, I felt heightened sensitivity to my inner world, with insights emerging through journaling, recalling experiences, group processing, meditation, and somatic practices.

A major realization was my fear of powerlessness in the unknown. As a result, I’ve developed ways to maintain the illusion of “in control”. While I might have previously chanted mantras of “letting go and acceptance,” this experience exposed my deep fixation on clinging to permanence, when life is inherent impermanence. My first psychedelic experience with MDMA had illuminated the importance of meditation, but true Ego Dissolution finally helped me embrace the vital role of mindfulness practice—specifically to embody the essence of surrendering, witnessing, and “non-doing.” Timothy Leary wrote that ego death can lead to a profound sense of interconnectedness, yet without surrender, resistance can spiral into panic, as I experienced firsthand.

Another insight was reclaiming my natural enjoyment of movement and dance. Despite participating in various dance performances growing up, I had internalized a belief that I needed to be exceptionally good at it—otherwise, I would expose myself to humiliation and judgment. The next day, as I felt the urge to dance, my inner critic whispered, “Don’t take up too much space.” During integration, I sat on my yoga mat and slowly stretched, exploring the somatic boundaries where my inner critic resided. Mindfully, I expanding my movements with intention—negotiating the tension between self-expression and self-doubt.

Finally, I developed a deep curiosity for the transpersonal realm—the space beyond the material world. While Western science and materialism assert that only what is seen and measured is real, my experiences, alongside others’ accounts, expanded my understanding of consciousness, interconnectedness, and ancestral heritage. I recalled my aunt acting as a medium, bridging the living and the dead. Initially shocked yet fascinated, I dismissed it as “archaic superstition.” However, this experience has since opened me to deeper curiosity and wonder about the vast unknown.

Final Thoughts

The use of psychedelics is by no means a shortcut to bypass the real work of tending to trauma, which often manifests as contractions in our psyche, body, and emotions. I believe the true value of psychedelic experiences lies in revealing the power of embracing the full spectrum of human experiences—the highs and lows—and, through self-reflection, transcending self-imposed limitations, rediscovering the light within us, and eventually fostering deeper connections with ourselves, others, and the world.